Colonialism, Capitalism, and Migration in Trinidadian Roti

By Philip Chivily

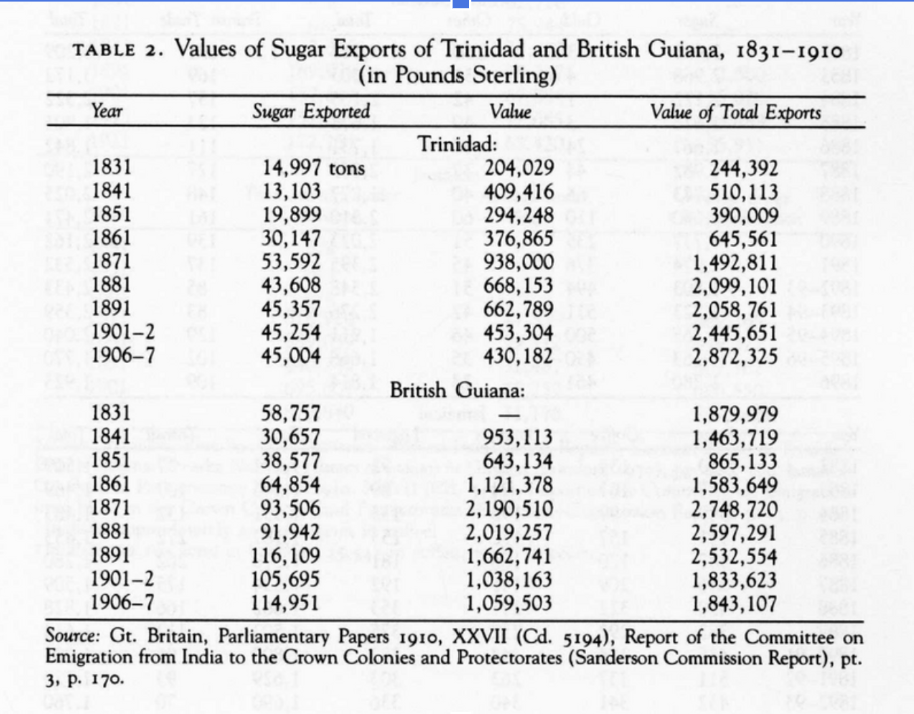

Trinidad is ideal to grow sugarcane,

which drew the attention of European colonial powers. Various European colonial powers invaded and occupied Trinidad; Great Britain wrestled control of Trinidad from France in 1797. The British inherited the old French plantation slave-based sugar economic system. However, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 outlawed slavery in Trinidad, forcing the British colonial elite to seek a new and inexpensive source of labor that could replace the now freed Africans. The British Raj became this source of labor; in 1845, the first South Asian indentured laborers arrived to Trinidad aboard the Fatel Razack. These migrants, as indentured laborers, signed unfair contracts which resulted in them receiving poor pay, and experiencing terrible work and living conditions in the Trinidadian sugar plantations. By 1870, British recruiting agents coerced over 42,000 South Asians, as Figure 2 shows, to sign indentured contracts to cultivate sugar plantations in Trinidad. This multitude did not just bring their industry, but also their food; the British would readily exploit their food to extend their control over their South Asian laborers.

Now, moving on to political and economic matters. Roti was an everyday and low-cost food for South Asians. However, the British colonial authorities had to import into Trinidad the necessary ingredients for roti, wheat and ghee, since Trinidad could not sustain wheat and dairy production. The British readily exploited this importation, through taxes on purchased wheat and ghee, and tariffs, levies, and dues upon imported shipments of wheat and ghee. Eventually baking powder underwent the same exploitative economic treatment as wheat and roti, at the same time South Asian indentured laborers in Trinidad began incorporating baking powder into roti, breaking with usual tradition of leaving roti unleavened. The British colonial administrators, were also cognizant of the fact that a hungry laboring population in a colony was likely to revolt and therefore stop the production of sugar and wealth, made an effort to feed the masses with food curated to resemble their diet from South Asia in easily accessible locations, at least for a little while. The British colonial administrators used all the revenue from the wheat, ghee, and baking powder to fund the imperial system, and maintain quote unquote humanitarian colonial endeavors, such as the depots.

Here, a diagram by J. Geoghagen, a British colonial administrator, shows the usage of said depots. South Asian indentured laborers, compulsorily classified with the European cultural labels as either “rice eaters” or “flour eaters”, receive the same rations, except that rice eaters receive rice while flour eaters receive flour. The flour eaters, receiving ghee, would have used their flour and ghee rations to make roti. One can imagine the women in their kitchens painstakingly turning their rations into roti. With a continuous supply of wheat and ghee, South Asian indentured labourers were able to continue to make roti, and in a new environment, the roti evolved. New roti forms emerged, such as buss up shut roti, and transportable roti for future consumption.

Starting in the mid-20th century, many Trinidadians began to migrate throughout the world, entering into the metropoles of the major colonial regimes. These migrants became the Trinidadian diaspora. The migration out of Trinidad intensified following Trinidad’s independence from the United Kingdom in 1962, and many Trinidadians settled in cities such as London, New York, Miami, and Toronto. Trinidadians, separated from their island home by thousands of miles, used food as a unifying force to tie the bonds of community together and maintain a distinct cultural identity. Wherever Trinidadians moved, they opened eateries, serving roti not too different from roti made in Trinidad. Here is a photo of roti wrapped around curried chicken I had for dinner. Today, in the Age of the Internet, Trinidadians, in and out of the diaspora, share roti recipes throughout social media, communicating new ways of roti-making to a vast audience. This is not the end of the story of Trinidadian roti; it is but another step in a story of migration and evolution that will continue as long as there are people who still make it. Through examining the role which roti and its ingredients played throughout Trinidadian history, one can see how the lives and unbalanced power dynamics between colonized persons and colonizers, and how diaspora populations operate in new and distant lands.

About Phillip

- Hamilton College ’23

- Major:

- What is he doing now:

- Why did he choose this topic?